Login

Registered users

High-rise dominant cities

The 20th Century was marked by the emergence of cities. Over the course of the century, the world’s population grew from 1.6 billion to 6 billion, which inevitably led to urban densification of cities to accommodate this population increase. According to the survey by the United Nations in 2018, 55% of the world’s population live in cities. As of 2018, Japan’s urbanization rate has been as high as 92.49%.

It is true that living in a city is very appealing. Young people especially can lead their own lives, free from the constraints of community and families in the countryside. Modern cities offer abundant material supplies and convenient transportation. This is why people rushed into cities.

The development of cities was amplified by the philosophy of modernism, which:

1. condones egoistic individuality;

2. releases people from communities;

3. conquers nature with technology.1

Two master architects of the 20th Century, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, described the cities of tomorrow in line with the thinking of modernism. Mies proposed skyscrapers made of iron and glass, while Le Corbusier envisioned an abundant green city with high-rise offices and housing. During the 20th Century, almost all cities were developed based on their vision.

However, as we approached the end of the 20th Century, the verticalization of office buildings and housing escalated beyond control. Although this may also be a consequence of population densification, global economy was the major reason behind the dominance of skyscrapers: to achieve maximum profit from a scarce commodity - land - it was necessary to build vertically.

Large scale redevelopments are underway in Tokyo today. One of the biggest downtowns in Tokyo, Shibuya, is known as a town for youngsters. The multiple train lines - JR (Japan Railways), subways and private railways - carry some 2.8 million passengers through it each day. Originally, Shibuya Station was built on the plain of the Shibuya River valley. Today, a variety of roads and streets run either along the river or radially to it. This has made for streets of diverse character, several of them forming vibrant neighborhoods frequented by young people. Major redevelopment is currently ongoing with Shibuya Station as its center. Three 200 m-tall towers have been completed, with a few more to follow in coming years.

However, the redevelopment projects are creating a so-called “urban core” consisting of interconnected pedestrian decks connecting multiple high-rise buildings. Restaurants originally located on the ground floor have been moved to deck level and pedestrians are forced to move further away from the ground. Shops with no relationship with the ground have discarded their original character and become anonymous emporia.

Unlike European cities that have public squares and plazas, in Japan the streets are considered public space. Each street has its unique character and embodies history. The streets in Shibuya are no exception; each street has its own personality and attractiveness, which was what made Shibuya a fascinating town. This fascination is being lost on account of redevelopment.

Homogenization is a consequence of modernism. The idea that nature can be conquered by technology results in verticalization and the creation of an artificial environment cut off from the ground, away from nature. Monotony is the inevitable result when offices and apartments are stacked vertically. In Tokyo today, high-rise condominiums are called “tower mansions” and living on the upper stories is a status symbol, the beautiful views from these higher levels commanding higher rents. However, these tower mansions do not offer operable windows or accessible terraces. Living in a skyscraper means living far away from the ground with little contact with the towns and its streets. The result is isolation.

50% of the family units in central Tokyo consist of people living by themselves. Most of them moved from the countryside to seek a new life in a big city. Although they have probably been blessed with the privileges of the city, at the same time, however, they experience the loneliness of solitude. How can they overcome this isolation?

Shared house and shared office

There is a tendency for young people in big cities today to share houses and offices. Not able to own or rent a tower mansions, some may, however, share offices in a high-rise building for economy reasons especially.

However, the notion of “sharing” has now lost its original intent of economic efficiency. People who share a house or an office have found a more positive meaning to “sharing”.

Residents get to know each other, cook for each other and even have parties together in a shared kitchen-dining room. Shared offices, mainly used by start-ups, allow people get to know each other, sometimes even starting projects together.

Young people today are now rediscovering how to enjoy city life, resisting the tower mansions and tower offices of the global economy.

Public architecture as “Home-for-All”

My office has been working on public architecture projects in Japan since 1990s. Each project, especially the libraries, is visited by many citizens everyday.

20 years have passed since the opening of Sendai Mediatheque and the “Minna no Mori” Gifu Media Cosmos which have more daily visitors than expected. From diverse backgrounds - children, mothers, students, and the elderly - they all share one space forming a large “family vessel”.

This was made possible because the spaces are not divided by function but remain one large space not unlike a park, offering diverse scenes. Not all visitors come here just to read books. Children can run around to some extent, while some people even take a nap on a sofa. They are public spaces where you can choose your preferred place depending on how you feel at the time, just as in a park.

A user questionnaire revealed the reactions of visitors of different age groups to these spaces. The elderly feel they are with their grandchildren, while students feel a sense of relief to be in the presence of people other than their peers at university.

Following the great east Japan earthquake, we have been working on the “Home-for-All” project: a small timber “gathering” home where people affected by the tragedy can come together. Similar “Home-for-All”s have been built for towns in Tohoku, struck by the tsunami in 2011, and for temporary housing units following the Kumamoto earthquake in 2016. Made of wood and only about 40 sq. m, they are widely used by local residents who meet regularly to share a meal or hold small events such as movie screenings, in stark contrast to the formal government-built communal halls.

Most people in the disaster-stricken areas are elderly farmers or fishermen living alone. In these communities the “Home-for-All” facilities are fully utilized as a communal space to heal and offset loneliness. They can truly be called a fundamental form of public architecture.

Likewise, the public architecture, such as the libraries mentioned above, can also be considered as a large “Home-for-All” serving the same purpose. Over and above its particular function, all public architecture should be a “Home-for-All” for those forced to spend a lonely life in big cities.

1 Hitoshi Imamura, Kindai no Shisou Kouzou (Structure of Modernism), Jimbun Shoin, Kyoto, 1988

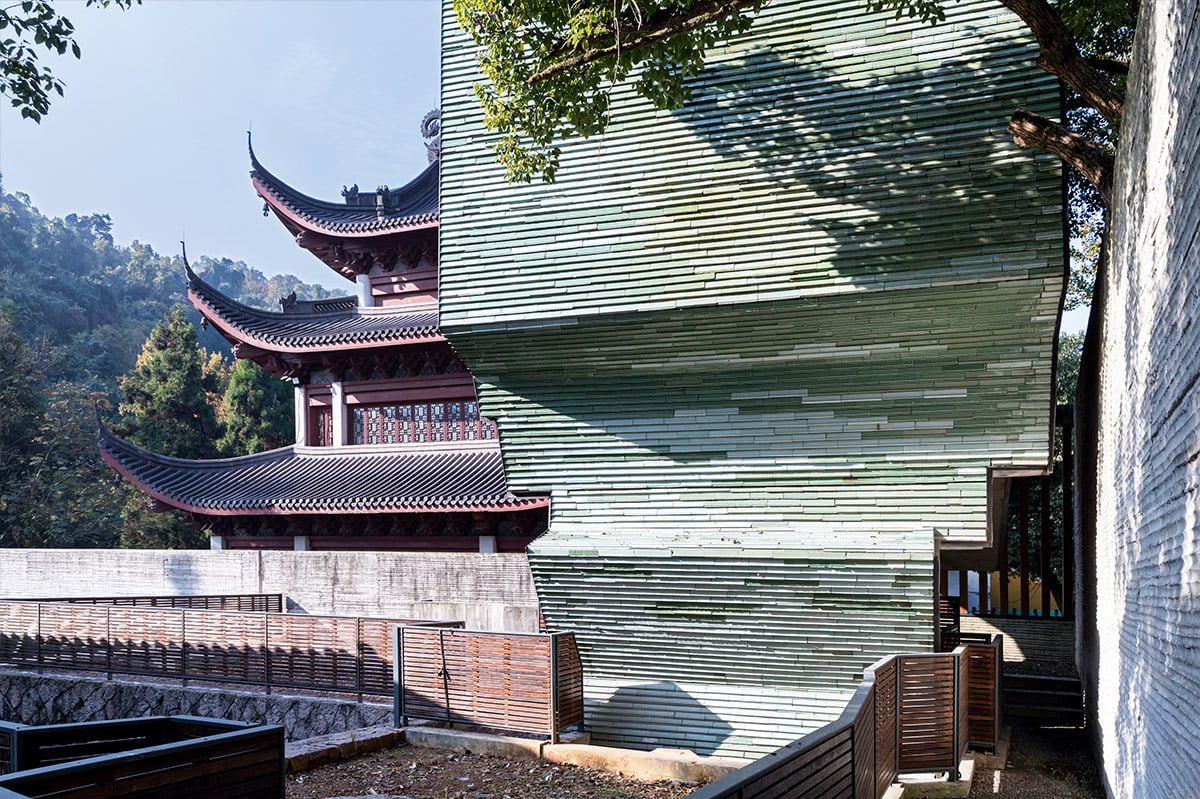

Lingyin Teahouse and Guest House

Amateur Architecture

Contemporary and the traditional are inseparable in this Tea House by Amateur Architecture in Hangzhou...

The Need for Awe

Nemesi Architects

A practice profile of Nemesi Studio, with focus on the residential complex Yun Xi Jin Ting Center in Shenzen...

A Strong Sense of Place

Trahan Architects

Six buildings and projects are explored in this survey of new work by Trahan Architects, among the top design firms in the United States...