Login

Registered users

For me, architectural drawing has always been not only a means of communication but also an important method of studying the environment of modern cities and reflecting on what architecture is all about in this days and age when the multifaceted nature of its development has reached its peak. And here I cannot completely detach my drawing practice from my work as an architect; at the root of both these activities is contemplation on one and the same topic: how to make cities attractive; how, without blind imitation and copying, to create surroundings that measure up to the best historical examples in terms of quality and visual intrigue.

I have to acknowledge that like the vast majority of contemporary drawing artists, I am much more willing to turn to the romanticism of ruins and ancient architecture. The reason for this is perfectly understandable - historical architecture appeals to the eye for its substantiality, its great attention to detail and, as a consequence, its ability to age in a beautiful, dignified way. That said, we all understand that contemporary architecture has totally different aesthetics. We wear different clothes; we do not ride in encrusted carriages but in fast-moving cars and in even faster-moving trains, and use all kinds of gadgets. And the architecture of the world we live in today with its crazy speeds has become completely different. Why then does it excite the pencil less often and less frequently prompt the desire to draw?

The fact is, in my view, that the surface density of contemporary architecture is much lower. Compared to the vast number of layers typical of historical buildings, contemporary architecture has literally only two to three lines that essentially delineate the architectural volume proper. I am extremely interested in exploring the correlation between these two worlds. For example, the drawing that I made last year in Mumbai captures, in the truest sense of the word, the clash between a Victorian structure and a modernist building from the 1960s that bumps into the historical volume. I use this drawing fairly often in my lectures to demonstrate how contemporary structures differ from historical ones, and to what degree modernism is keen to use purity of technique and laconism of form. Modernist architecture is minimalist and elegant, a tradition going back to the 1920s, beginning in particular with the buildings by the Russian constructivists: the Zuev Club on Lesnaya Street in Moscow (architect Ilya Golosov, 1927-1929), or the Rusakov Club on Stromynka Street in Moscow (architect Konstantin Melnikov, 1929) are excellent examples of this.

If you compare this architecture to the frequency and density of lines intrinsic to historical structures, as a drawing artist you immediately find yourself face to face with the utterly laconic surface of modernist façades and unable to find any “peg” on which to hang your interpretations and renditions. When you draw (or, for that matter, design) such architecture, it is rather easy to commit inaccuracies. This is even more the case with the architecture of late modernism, characterized by a combination of large laconic forms and works of monumental art. As is known, this architecture was developed all over the world, and socialist countries were especially active. I had the opportunity, for example, to draw the University of Mexico administration building with murals by David Alfaro Siqueiros. I also have a fantasy drawing on the theme of city blocks, illustrating modernism’s artistic and decorative approach to the decoration of vast planes. As we know, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union such architecture receded into the background, fading from the sight of art historians, not to mention the general public - unfairly, in my view, given its artistic merits. In Germany, some buildings with modernist façade friezes and decorative panels are now gradually finding themselves on the protected buildings list. Indeed, I believe the movement to preserve these striking monuments of past times should become standard practice.

When talking of the expressiveness of modernism and the opportunities opened up to a drawing artist when he finds himself one-to-one with the best examples of this style, mention must be made of the buildings of Oscar Niemeyer. His creative work was for a certain period an unbelievably interesting subject of study for me. I traveled to Brasília to see his buildings at first-hand and draw them. It was an extremely important experience and I recommend that anyone who wants to work in architecture make such a trip: only after actually seeing these icons of modernism - how they live and how they age - and after correlating their scale level with yours can you understand the language of contemporary architecture. For example, from the outside, the Cathedral of Brasília because of its utterly laconic form and its few simple lines does not look like a sacred building at all, but once inside you find yourself totally captivated by a huge, light-filled space. Similarly, the National Congress building. Strictly speaking, it does not have a single detail for the eye to latch on to, its architecture of pure forms so clearly precise as to seem alien. During that trip I was fortunate to meet Oscar Niemeyer himself. He told me that his architecture was akin to the “Copacabana Ridge” - a smooth line of ascents and descents that could be seen from the bay window of his studio in Rio. Take a look at his buildings and you will see what he meant. Whether it be the blend of large sculptural volumes as in the parliament building or the colonnade in the shape of a soft parabola at the Palácio da Alvorada, it is a triumph of a form devoid of any detail. Likewise the Niterói museum in the namesake city, my drawing of which was in fact once used as an illustration of an unearthly landscape in an exhibition of works by scenographer Ken Adam. Incidentally, Niemeyer’s architectural language, in the very short period of time spent on the Brasília center construction, “hummed” the tunes of virtually all architectural hits with various curvilinear volumes, which are still widely used to this day. Look at the forms of modern skyscrapers and the contemporary art museums that are so popular nowadays that each more or less well-off city deems its duty to set up.

Modernism has left us a legacy of huge dimensions, but, alas, its mass very rarely makes one feel like drawing, finding interesting perspectives, and sharing a “picture of the city”. One of the exceptions to this that I know of is the French city of Le Havre. As is known, it was severely damaged by bombing raids during World War II, and in the postwar years the central part of the city was rebuilt to the design of Auguste Perret. Oscar Niemeyer’s Le Volcan cultural center has become one of Le Havre’s symbols. The building is arranged in the manner preferred by the architect: entering from the main square, you go below as if into the depths of space to find yourself in a world completely isolated on all sides, from which grow mighty forms seemingly devoid of scale and details. In 2005, UNESCO added the center of Le Havre to the World Heritage List for “the innovative exploitation of the potential of concrete”. This is one of the rare modern World Heritage sites in Europe and I hope we will have more with time.

Among the topics that interest me most as a drawing artist are the so-called icons or centerpieces, buildings that definitely stand out against their surroundings. As a rule, they are building-sculptures of decidedly distinctive form, which serve as an expression of and are due to the unique functions they perform within the structure of the city. While in past ages the role of such structures was typically played by cathedrals or main administrative buildings (such as town halls) or royal palaces, nowadays the typology of icons has shifted towards corporate headquarters and, of course, cultural sites - primarily museums, including contemporary art museums - whose buildings are often more impressive and profound than the exhibitions they show. Of course, a textbook example that comes to mind right away is Frank O. Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Last year I specifically went to Bilbao to see how the museum is doing after more than 20 years since its opening. Naturally, I not only saw the famous building but I also made a drawing of it. The building and the sculpture by Louise Bourgeios standing in front of it perform a kind of dance of forms, free of course of any customary amount of detail.

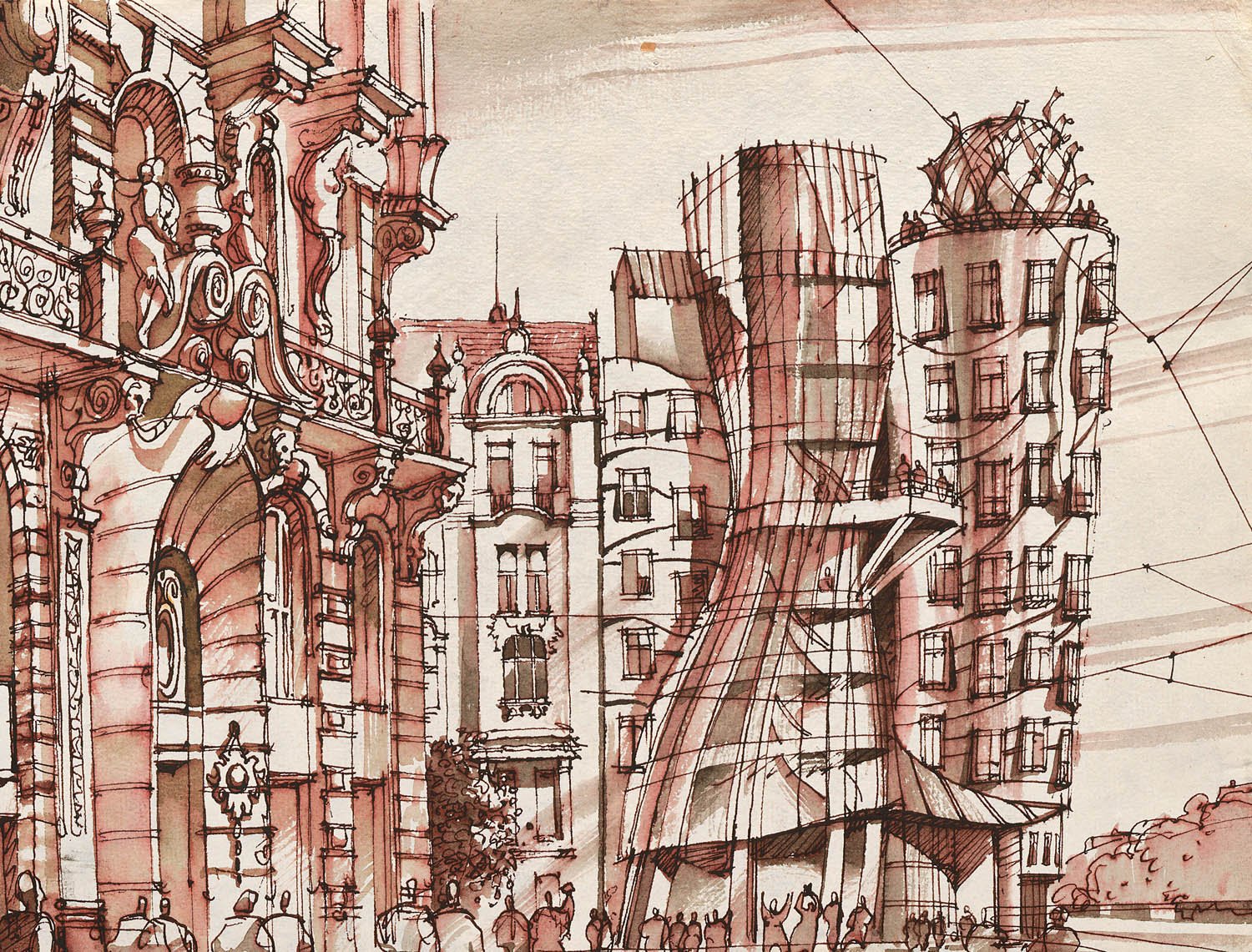

Another building by Frank O. Gehry related to the theme of dance - maybe even more so than the museum in Bilbao - is the Dancing House in Prague, which was initially designed as an office building but ended up as a hotel. Facing the Vltava River embankment, the building is designed in the form of two cylinders, one made of concrete and expanding upwards, the other fully glazed and widening out downwards like a skirt fluttering in the wind. The “dancing” façade is built out of 99 distinctly shaped pre-fabricated concrete blocks. Curiously, for several years after the end of construction, the building was heavily criticized by Prague’s public who believed “its tipsy look” to be an insult to the city and especially to the nearby townhouses. Although with time this building has been recognized as one of the symbols of Prague, I must say I continue to regard it as controversial. Of course, it is striking in its form, but due to its very fragmented yet over simple details, it creates the feeling of being a disappointing resemblance that fails to measure up to its historical surroundings.

In this respect, a completely different result can be achieved if the building totally contradicts the historical surroundings in every detail - from its form and positioning in the area, to its door handles. For me, one such example is the Centre Pompidou (architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, 1977) in Paris. As you know, the revolutionary nature of the project was the idea of bringing all engineering utilities out onto the façades of the building, from the escalators and elevators to the ventilation ducts and water pipes. In this way, the architects not only made available the absolute maximum space for exhibiting art but also pointedly renounced the idea of the museum as a closed “box with valuables”. The building, whose façades are a tangle of pipes, ducts and components of different thickness, defiantly presents a sharp contrast with its historical surroundings, loudly proclaiming itself conspicuously modern and independent, exactly as the art exhibited within its walls.

Renzo Piano interpreted the NEMO Science Museum in Amsterdam in an entirely different way, contrasting the multifaceted historical environment with an uncompromisingly monolithic form. It is extremely interesting to draw such themes because for me this sort of contrasting combination of history and modernity reflects all the controversies of contemporary architecture. This is a very well known theme in the Eternal City of Rome. The MAXXI building by Zaha Hadid Architects is a series of elongated freely intertwining volumes while the frontage on Guido Reni Street has preserved the historical façade of the former barracks. Only on entering the museum gates does one realize the plasticity and fluidity of the modern concrete forms - overhanging the courtyard is an impressive console, its glazed end reflecting “traditional” Rome.

Of course, in terms of contemporary architecture to be cognized with the help of a drawing, of particular interest are the megalopolises of Asia and the Middle East, which have chosen a development path far from the ideals of European urban planning. Made up of essentially different scale spaces, these cities have an affect on people through megastructures - whether buildings, traffic interchanges or large-scale installations of neon signs. It is a kind of still life of objects where light, form, and plane surface play a tremendous role and details play a much smaller role. As I try to feel and comprehend these spaces with my hand, I am simultaneously looking for techniques that best convey their character and appearance. If in European cities I work mostly with pencil and pastel, for the soaring forms of Niemeyer Sennelier Gris ink proved ideal. Although an intense color, with the help of water it becomes practically transparent, conveying the feeling of the weightlessness of modernist structures. On the other hand, neon felt-tip markers turned out to be the most suitable for drawing billboards and LED screens, ubiquitous features of the image of streets and high-rises in many megalopolises.

I think we need to draw contemporary architecture for there is no other more convenient and sure way to understand how it is arranged and what laws underpin its development. True, historical monuments and numerous background buildings of ancient cities are more pleasing to the eye and more gratifying in sketchbook depictions, but it is not enough to study the laws of harmony of the past without understanding the laws of harmony of the present. How does historical and contemporary architecture interact with one another? Today, examples of this interaction are found mostly in areas of sharp contrasts. Should this be the only way? Frankly speaking, I am convinced that such unions can be softer and more harmonious.

“We live in an era of vanished picturesqueness of architecture. Its picturesqueness has vanished together with order, decorations, reliefs and ornaments. Defiance and radical dialogue have settled on top of it, whereas the outskirts were taken over by the faceless, pragmatic, devoid-of-beauty (a forgotten word in regard to architecture!) form of minimalism”. This is a quote from my book 30:70. Architecture as a Balancing Act, which I co-authored with the art historian Vladimir Sedov. The book is exactly about the direction in which contemporary architecture can develop, above all regarding background architecture, which accounts for the bulk of residential and office construction taking place today, in order to provide visually rich and harmonious surroundings for outstanding individual buildings that exemplify the technical and artistic achievements of their time. The conclusions I have reached over the course of this study were certainly assisted by my use of drawing. Investigating the city with the help of pencil and paper, I not only better understand the nature and laws of the formation of the contemporary urban environment, but I also look for specific solutions, which I then implement as an architect, and which I hope will lead to a harmonious and comfortable city, not only on paper, but in real life.

Leaving a mark on the landscape

Giovanni Vaccarini

Architect Vaccarini’s Powerbarn is a remarkable example of how a new industrial project on a remediated brownfield site can give rise to a striking ...

San Filippo Neri Care Home

Picco architetti

Picco Architetti’s contemporary architecture additions have breathed new life into an ancient structure, turning a former monastery and later boardi...

Office complex “The Corner”

Atelier(s) Alfonso Femia / AF517*

The Corner building by Atelier Femia is in the center of the New Milan, close to Piazza Gae Aulenti and the Bosco Verticale tower...